IRSF and Wangiri types of fraud are generating huge losses for consumers and network operators alike. These types of fraud are not particularly sophisticated or complicated to carry out.

About 13 years ago, a good friend of mine, who was the head of anti-organised crime in the area where I live, contacted me. His organisation also fought against internet crime and cooperated strongly with other states, sharing information to catch bad actors. One day, he called me and asked if I could help one of his prosecutors understand and explain to a judge how someone had made about 5 million USD from a fraud they had not encountered before. They had intercepted many messages, IP packets, and computer logs, and had followed a money trail. As everything was on paper, it took me a while to understand and explain it.

The fraudster was very organised and operated this fraud for about a year or so. I will briefly explain what he did:

He exploited a zero-day vulnerability in the Asterisk PBX and began scanning hosts for this vulnerability. Once a host was found, he hacked it, installed a rootkit, and an IRC bot that would connect to his IRC channel to receive commands. Each hacked machine would then start scanning for other hosts with the same vulnerability, behaving like a worm and operating autonomously, all with automated scripts. The fraudster would then check his IRC channel to see how many machines he could fully control.

He visited one of the thousands of websites that advertise the sale of IPRN (International Premium Rate Numbers) and obtained some test numbers from there. I will explain later how these work.

He then issued a command on his IRC channel for all his hacked machines to call the test numbers and see if they connected to the IPRN provider. Those who successfully connected to the IPRN provider were added to a group. He reserved numbers from those ranges and issued commands to the IRC bots so that the hacked machines would call those numbers (he cleverly parameterised the scripts—such as how many calls to make in parallel, how long the calls should last, etc.).

By being paid by the IPRN provider, he made around 5 million USD, and he was eventually caught because of the money trail.

IPRN numbers are either real numbers or even fake ones that are advertised by IPRN providers to voice transit carriers as belonging to them. In an ideal world, any transit carrier would accept such numbers as being lawfully allocated to the IPRN provider, although this doesn’t always happen.

If you make a call from your phone to one of these IPRN numbers, and if, along the call path, there is a transit carrier that has an agreement with the IPRN provider, the call is routed to you or to an IVR, and the IPRN provider will pay you a portion of the international termination rate. This is generally long-distance as operators have local and regional interconnects that won’t go through those transit carriers.

The technique I described earlier was IRSF. Wangiri works in a very similar way, but you don’t have to hack any machines. Here’s what you would do:

Then, it’s a numbers game. X number of users would see missed calls from that Somali number, Y% of them would call back, and they would have an average call duration of Z minutes. The IPRN provider will then pay your share of the termination call to Somalia for X * Y% * Z minutes. If you adjust the variables, you can make a significant amount of money.

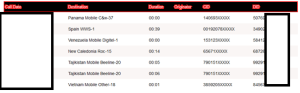

I logged in to an IPRN provider, obtained a Denmark number (anonymised below) that was live, and called it—it rang until I reached a voicemail (a standard one). Below is the number (anonymised) along with our live service response. To note, before that, I called another IPRN Denmark number where a regular person answered

{ "454271….": {

"cic": "45521",

"error": 0,

"imsi": "23806XXXXXXXXXX",

"mcc": "238",

"mnc": "06",

"network": "Hi3G (Three Denmark)",

"number": 454271….,

"ported": false,

"present": "yes",

"status": 0,

"status_message": "Success",

"type": "mobile",

"trxid": "BWMp13y"

}

}

I checked the latest test calls on the IPRN site and couldn’t find my call—which means the calls I made did not reach the IPRN provider, as they didn’t go through any of the transit carriers that have an agreement with this provider.

So, this is an advertised IPRN number, but I’m charged a normal rate.

A simple example: you make 100,000 flash calls, 20% of the recipients call back and spend an average of 2 minutes on the line. You make $1,200 – but the people calling would probably pay ~ $0.5/minute, so the overall fraud amounts to $20,000.

We work with a few companies that scrape as many IPRN provider sites as possible and create a database of those numbers. At the time of writing this post, the current number of entries in the IPRN table is 20,073,001, of which 13,518,172 (67%) are valid numbers.

This database can be purchased as a download or queried through our Teleshield Fraud Service.

The data can be used to identify and block calls in response to flash calls from IPRN numbers, shorten call durations, limit the number of calls to IPRN numbers, and more.

Last updated on August 5, 2025

If you're struggling with IRSF or wangiri fraud, our IPRN database can be purchased as a download or queried through our Teleshield Fraud Service. Meaning you can easily block the right calls before losing money.

Speak to a TeleShield expertWe provide the most comprehensive device, network and mobile numbering data available

Contact us > Chat to an expert >